“Rivers are the arteries of our planet; they are lifelines in the truest sense.” – Mark Angelo, Founder, World Rivers Day

This August I took my environmental values on the river. As a participant in the Rivershed Society of BC’s Sustainable Living Leadership Program I canoed and rafted the length of the Fraser River. At 1375 km, the Fraser is the longest river in BC and drains about a quarter of the province’s land mass.

We stopped in eleven vibrant communities along the river, where I spread the word about West Coast’s free environmental legal aid services and learned about the important work that local environmental advocates were doing. The 27-day journey was challenging and beautiful, and I got to spend that time with a group of the most amazing people who are passionate about protecting our waters. One of the most inspiring was Keely Weget-Whitney, who swam two days along the Fraser to show her love for and solidarity with the salmon.

We started in the headwaters of the Fraser, in Mount Robson Provincial Park in the Rocky Mountains. It was a sunny day and Mount Robson appeared without its usual crown of clouds.

Mount Robson is so big that it creates its own rainshadow, sheltering a patch of inland temperate rainforest in the heart of the Rockies. Inland temperate rainforest is extremely rare globally – in North America, it only exists nestled beneath the Rocky mountains in an arc from Idaho to Prince George. BC’s portion of the inland rainforest has features that are unique from any other ecosystem in the world. The combination of coast-like humidity with high elevation makes our inland rainforest perfect habitat for endangered mountain caribou, and you know how much we love southern mountain caribou. It is also important habitat for threatened grizzly bears, wolves, and wolverines.

We put in near Tete Jaune Cache. At its headwaters, the Fraser River runs glacier blue.

(Photo: Erica Stahl)

(Photo: Erica Stahl)

(Photo: Erica Stahl)

We canoed down the headwaters for three days, then we took a quick detour to spend some time in the wilderness of the Goat River. The Goat River is a largely pristine tributary to the Fraser and another example of rare inland rainforest. The Goat is a spawning ground for Chinook salmon – Southern Resident orcas’ primary food source. While we were there, we helped the Fraser Headwaters Alliance with trail building along the Goat River Trail, an old supply trail from the gold rush era. The trail is part of the Fraser Headwaters Alliance’s work to protect the Goat River watershed and link the West Twin Protected Area, Bowron Lakes Provincial Park, and Ptarmigan Creek Provincial Park to create one connected wilderness area.

Roy Howard of the Fraser Headwaters Alliance poses on a newly built boardwalk along the Goat River Trail (Photo: Erica Stahl)

After our time in the Goat River valley we shuttled down to Quesnel, keeping an eye on the wildfires the entire time. After Quesnel we switched over from canoes to rafts so that we could navigate the rapids of the Fraser Canyon.

This is where Keely did her swim. She swam nearly 110 km from Lillooet to Tuckkwiowhum (Boston Bar) over two days under smoky skies to attract attention to the plight of wild salmon and the river they depend on.

The Fraser is a powerful river. Its currents are strong and it’s full of eddies that can suck you in and keep you spinning in circles. It’s hard enough to swim it when it’s calm – I know because I tried. Keely is a powerful woman to have swum with it for so long. In Keely’s words, “I just feel that if I care, a young Indigenous Stl’atl’imx mother, people will reflect on that, and they’ll say why am I not caring, what can I do for a change?”

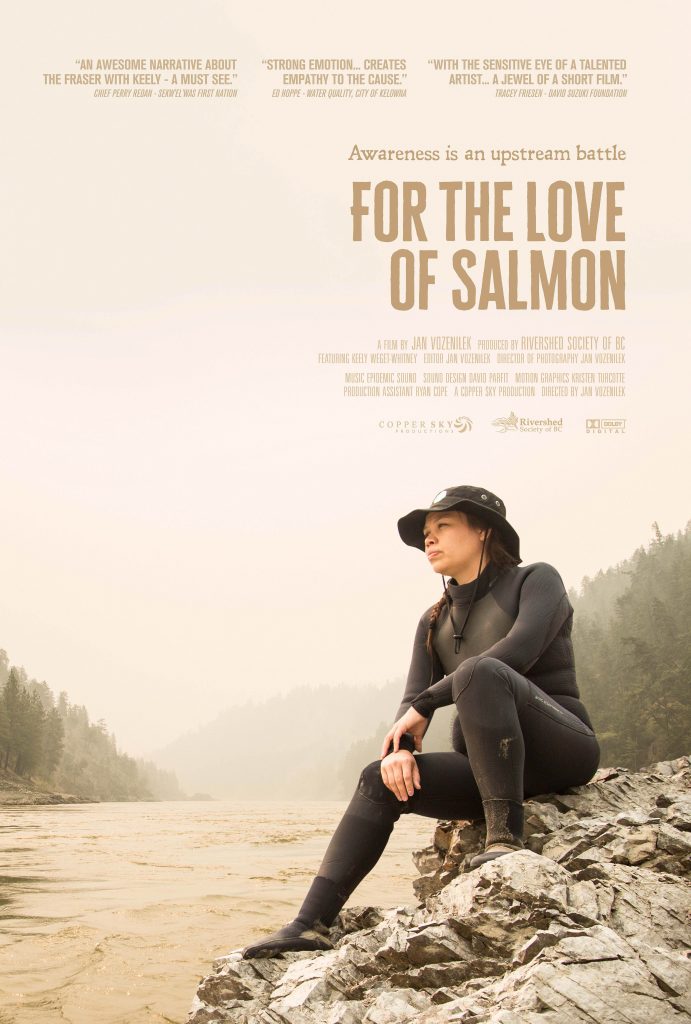

Keely’s work is attracting notice. The film “For the Love of Salmon,” which follows Keely during her 2017 swim, has now been recognized for three awards including:

- Pinnacle Award: Short Film, Elevation Indie Film Awards, Dublin Ireland;

- Audience Choice Award for Best BC Film, Moonrise Film Festival, Wells BC;

- Special Jury Award; Cinemuskoka, Muskoka, Ont.

My other main memory of the Fraser Canyon is the smoke. It was everywhere – it burned our throats, stung our eyes. I developed a nasty cough that went away when the smoke finally cleared. When we stopped in Williams Lake it had some of the worst air quality in the world.

This was a sunny day, apparently! (Photo: Erica Stahl)

Climate change impacts would be a constant theme on the trip. Evidence of last year’s wildfires was all around us, and most of our time on the river would be obscured by smoke. Longer, fiercer wildfire seasons are a marker of climate change. The smoke was so thick that it blocked much of the sun’s heat, leaving us bundled up in toques and balaclavas in the middle of August. The irony wasn’t lost on us.

With wildfires along our route, I found it unfair that communities should have to foot the bill to prevent climate impacts every season, while fossil fuel producers pay nothing. This sentiment is one that many cities, including most recently Whistler and Squamish, are adopting by sending Climate Accountability Letters to 20 major corporations to pay their share of climate costs.

Our protection from the smoke (Photo: Oliver Berger)

The apocalyptic colours on the river (Photo: Ella Parker)

When the landscape made the sun look as if we were on Star Wars' Tatooine planet (Photo: Brock Endean)

There were times when the smoke cleared enough that we could see a little bit of the beauty around us.

When the smoke cleared briefly in the canyon (Photo: Brock Endean)

A black bear cub spotting the camera in the Fraser Canyon (Photo: Lisa Bland)

Can you spot the bighorn sheep? (Photo: Erica Stahl)

By this time we’d reached the lower Fraser River. In Hope we switched back to canoes and paddled for five days to reach Vancouver. The river is much more polluted at this point, having picked up waste from human activity all along its route. Even so, there was so much wildlife. We saw seals swimming upriver as far as Hope, chasing the returning sockeye. A white sturgeon breached right in front of our canoe, a beaver greeted us in Langley, and of course there were eagles. One of my favourite sights was the people out in droves fishing for salmon after years of fishery closures.

What if the salmon runs were restored so that every year could be an abundant salmon year? Imagine what this part of the river could be like if it were cleaned up! It’s an exciting thought.

All too soon, we were at the end of the trip. For me, paddling out the mouth of the Fraser into the Pacific Ocean was also a homecoming. I live in Vancouver, and the river I had met in the Rocky Mountains had taken me home.

Vancouver as seen just past the mouth of the Fraser’s north arm (Photo: Brock Endean)

Spending almost a month on the river shifted something in me. I realized that before, my relationship with the river and most of its communities had been abstract, even though I grew up minutes from the Fraser’s banks as it runs through Vancouver. The river had always been something that I drove over or walked beside. Now I understand in my bones that this river gives us life.

The river that I grew up calling the Fraser has many names. “Stó:lō” is the Halkomelem word for the Fraser River, in the Dakelh language its name is Lhtakoh, and the Tsilhqot'in name for the river is ʔElhdaqox. This river has sustained life since time immemorial. It is among the most important salmon rivers in the world, the home of the endangered white sturgeon, and an essential stop for migratory birds on the Pacific flyway.

And it needs your help.

As the liaison lawyer for West Coast’s legal aid services, I speak to many British Columbians who are concerned about the health of the Fraser and its salmon, and other freshwater sources across the province – people who want to prevent pollution from industrial activities like mining (Mount Polley’s effluent drains into Quesnel Lake, which drains into the Fraser), forestry, and oil and gas (the Trans Mountain pipeline would cross the Fraser more than once, and it’s not dead yet).

Thankfully, there are many organizations across BC devoted to protecting the Fraser and all the life that depends on it. The Rivershed Society of BC’s work to heal and protect the Fraser inspires me. Find an organization that inspires you and join it, or give to it, or join a river cleanup day. Most of all, get out on the river. I guarantee it will change your perspective.

(Photo: Brock Endean)

(Top Photo: Lisa Bland)